Bring Your Genes to Cal

On the Same Page gives new students in the College of Letters & Science something to talk about. This year, we’ll all be on the same page exploring the theme of Personalized Medicine—the set of emerging technologies that promises to transform our ability to predict, diagnose, and treat human disease—with Professor Jasper Rine as our guide.

The program announcement has already generated a lot of discussion and questions, about everything from our reasons for tackling this topic to the safeguards we have put in place for our students. Dean Mark Schlissel provides answers in the FAQ. See also his open letter below.

Participate in the Grand Experiment

All new L&S freshmen and transfers received a package in the mail over the summer. This package contained, among other things, a saliva kit and a consent form, along with a link to a video version of the consent form. Over 700 new students have sent us a small sample of their own genetic material (along with their consent form). Professor Rine will report the aggregate results of his analysis of three genes that contribute to the impact of nutrition on your health at his lecture on September 13. For more information on how the program works, see the Student FAQ. For details on the changes to the program due to a recent decision by the California Department of Public Health, see the letter Dean Schlissel mailed to students on August 13, or the press release from August 12.

As originally stated on the consent form, you are able to withdraw from this study without penalty or loss of benefits to which you are otherwise entitled. If you no longer wish to have your data included in this program, please place your original barcode in a sealed envelope addressed to “OPHS Director” and place it in a secure mail drop box just outside of the Office for the Protection of Human Subjects on the 3rd floor of 2150 Shattuck Avenue, Suite 313 between 7:00 a.m. and 6:00 p.m. Take care NOT to place any identifying information on or in the envelope other than the barcode itself. This must be done no later than this Friday, September 10. You can also mail or fax this information directly to OPHS (see http://cphs.berkeley.edu/contact.html for address/number).

News and Resources

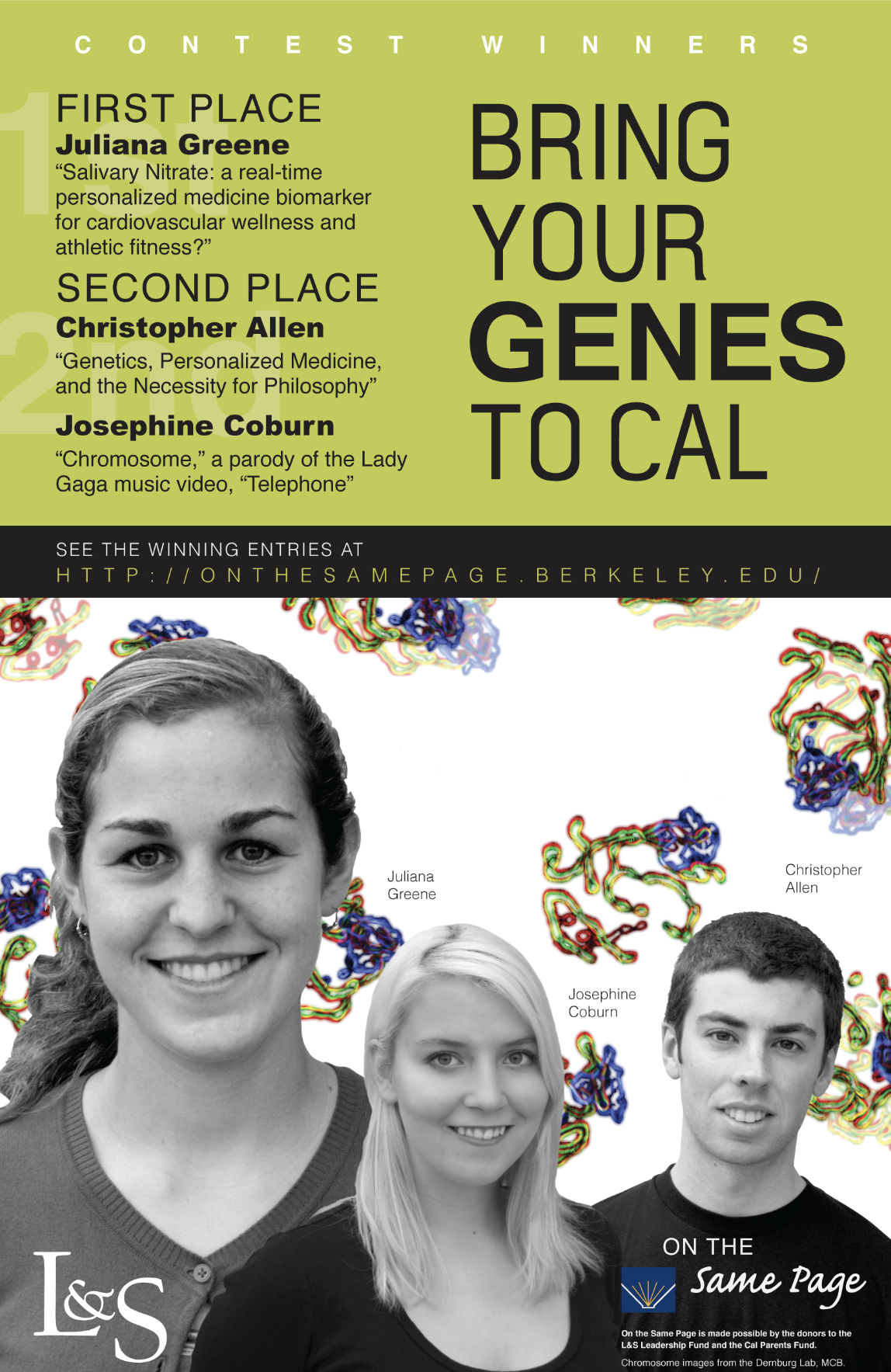

Research proposal, music video win prizes in DNA contest

By Robert Sanders, Media relations | JANUARY 26, 2011

Tempest in a spit cup

By Robert Sanders, Media relations | SEPTEMBER 10, 2010

UC Berkeley alters DNA testing program

By Robert Sanders, Media relations | AUGUST 12, 2010

Press Coverage

A topic as complex and far reaching as personalized medicine is bound to generate vibrant debate. The program announcement has already generated a lot of discussion and questions, about everything from our reasons for tackling this topic to the safeguards we have put in place for our students. Dean Mark Schlissel provides answers in the FAQ. See also his open letter.

Faculty members and students from across the disciplines will bring their perspectives and methodologies to bear on this debate come fall.

“Go To College, Get A Genetic Test,” KQED Quest Community Science Blog, June 4, 2010

“UC Berkeley offer to test DNA of incoming students sparks debate,” Los Angeles Times, June 1, 2010

“Unwinding Berkeley’s DNA Test,” Inside Higher Ed, May 28, 2010

“College Bound, DNA Swab in Hand,” New York Times, May 18, 2010

“L&S Freshmen Can Have Their DNA Analyzed,” The Daily Californian, May 17, 2010

“The DNA Assignment,” Inside Higher Ed, May 18, 2010

“UC Berkeley plan test student DNA raises alarms,” San Jose Mercury News, May 20, 2010

“Ethics of UC Berkeley’s gene testing questioned,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 21, 2010

“Incoming Cal Freshmen Asked For DNA Samples,” KPIX Channel 5 News, May 18, 2010

“UC Berkeley Asking Incoming Students For DNA,” KTVU Channel 2 News, May 18, 2010

Events

Looking for the Good News in Your Genome: A keynote lecture by Professor Jasper Rine

Monday, September 13, 2010

7:30 p.m.

Wheeler Auditorium

The kickoff event for the 2010 On the Same Page program in the College of Letters and Science. This event, and the Bring Your Genes to Cal program as a whole, was made possible by gifts to the L&S Leadership Fund, and cosponsored by the California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences (QB3).

Personal Genomics and Public Angst: A keynote lecture by Professor Alta Charo

Wednesday, September 29, 2010

7:30 p.m.

105 Stanley Hall

Direct-to-consumer marketing of genetic tests has brought fresh attention to old debates: Who owns our personal information? What obligations are placed on us to seek out and use this information? What limits are imposed on those who would use our information for their own purposes? And perhaps most important of all, what real value is there in this information? As we enter an era in which genetic information is used for everything from humanitarian efforts to identify victims of genocide to recreational geneology and ancestry exploration, has genetics moved beyond the world of medicine? And what in the world should we be doing about it?

This event was sponsored by the College of Letters and Science and California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences (QB3)

Screening of Jar City

Thursday, September 16, 2010

Nestrick Room, 142 Dwinelle Hall

Moderated by Professor Linda Rugg

Film Series

On the Same Page film series in the residence halls (open to all students). All screenings at 7:00 p.m.

Monday, August 30, Clark Kerr Campus Dining Commons

Wednesday, September 8, Unit 4 Academic Services Center

Thursday, September 9, Unit 1 All Purpose Room

Friday, September 10, Unit 2 All Purpose Room

Saturday, September 11, Unit 3 Academic Services Center

The DNA Age: Personal Stories from the Genetic Frontier

Monday, October 11, 2010

7:30 p.m.

Wheeler Auditorium, UC Berkeley. See map at http://www.berkeley.edu/map/maps/CD34.html

New York Times national correspondent Amy Harmon will moderate the panel, which includes two women Harmon wrote about in her Pulitzer Prize-winning series of articles, “The DNA Age,” that explored the impact of new genetic technology on American life.

The panel speakers are:

• Dr. Deborah Lindner, who tested positive for a DNA mutation that increases her risk of developing breast cancer

• Katharine (“Katie”) Moser, an occupational therapist who found out that she has a genetic mutation that dooms her to an early death from Huntington’s disease

• Anna Tague, a mother of four whose youngest child was born with a rare genetic disorder

• Dr. Steven Schonholz, medical director and surgeon at the Breast Care Center, Mercy Medical Center, Mass., and a national advocate for training physicians to incorporate genetic testing and informed consent into their practices

The panel discussion – the last public event in this fall’s “Bring Your Genes to Cal” program – seeks to shed light on the challenges new genetic information poses for all of us by exploring the personal stories of people who are grappling directly with its benefits and burdens.

Among the questions the panelists will bring up as they tell their tales are: How do you face the future at age 22 when you know you carry a gene for an incurable illness expected to strike in middle age? Would you eliminate your high genetic cancer risk if it meant undergoing surgery that can be physically and psychologically arduous? Where do you go when a test pinpoints the genetic cause of your child’s developmental differences, but offers little information about how to address them? How do family members respond to medical knowledge that may change their perception of themselves and each other?

Schonholz, a doctor who uses genetic tests in his practice, will offer his medical expertise.

The Experimental Man: Cutting-Edge Scientific Research and Implications for Personalized Medicine

Tuesday, November 9, 2010

6:30 pm

105 Stanley Hall

David Ewing Duncan may have one of the most familiar bodies in the history of humankind. Duncan has undergone numerous tests to determine his genetic background, calculate his exposure to chemicals, and scan his brain for levels of activity in different sectors—all in an attempt to figure out what the future holds for people in an age of personalized medicine. Join Duncan as he gives a lively talk on his journey to “physical self-discovery” to see what effects these medical technologies will have on individuals, families, and cultures.

Sponsored by UC Berkeley Extension

Contest: Show Us What You are Made Of!

Each of our students is unique—genetically unique but also uniquely talented. This year we are sponsoring a contest designed to showcase our talented gene pool.

Our theme for fall 2010, Personalized Medicine, is interdisciplinary. Scientists are clearly essential to explore the set of emerging genetic technologies that will transform our ability to predict, diagnose and treat human disease. But we also need the artists, philosophers, social scientists, and everyone else to bring their perspectives to bear.

Our students expressed their creativity in a remarkable array of contest submissions, ranging from jewelry in the shape of DNA to poetry. Three winners were selected:

First place:

Juliana Green, for a write-up of her original scientific experiment: “Salivary Nitrate: a real-time personalized medicine biomarker for cardiovascular wellness and athletic fitness?”

Two second-place winners:

Christopher Allen, for his essay entitled “The New Genetic Frontier: A Philosophical Perspective”

Josephine Coburn, for “Chromosome,” her parody of the Lady Gaga music video, “Telephone”

Congratulations, Juliana, Josephine, and Chris!

Frequently Asked Questions

The program announcement has already generated a lot of discussion and questions, about everything from our reasons for tackling this topic to the safeguards we have put in place for our students. Dean Mark Schlissel provides answers in this FAQ. If you are a student considering whether or not to participate, see also the Student FAQ.

Each year UC Berkeley looks for a theme for our On The Same Page program that would engage incoming students with our faculty in deep and meaningful discussion about important societal issues. Rapid advances in genetic technologies are ushering in an era of personalized medicine in which each individual’s genome sequence can be determined and used to help physicians better prevent, diagnose, and treat disease. To take full advantage of these opportunities, scientists will have to figure out new ways to decipher this genetic information and society will have to consider its implications. With great strength in the biomedical sciences and computational biology as well as in the social sciences and humanities, UC Berkeley is uniquely positioned to engage some of our nation’s brightest young students in a discussion of this new frontier. This type of broad, scholarly discussion of an important societal issue is what makes Berkeley special. From a learning perspective, our goal is to deliver a program that will enrich our students’ education and help contribute to an informed California citizenry.

There is an international effort known as the 1000 Genomes Project, directed at producing the complete genome sequence of 1000 individuals representing ethnicities around the world. Our own National Institutes of Health has set a goal of reducing the cost of sequencing an individual human genome down to $1000 or less, likely to be achieved in the near future, and is funding the sequencing of approximately 10,000 human “exome” sequences (an exome consists of the 22,000 genes in our genomes that provide the coding information for proteins). The National Cancer Institute has embarked upon the mission of sequencing the genomes of thousands of different examples of the most common human cancers to uncover the changes in genomes that lead to so much human suffering. Finally, our campus is within 50 miles of the companies producing the most innovative advances in genome sequencing technology. These advances are stunning even to those of us who use these technologies every day, and they have vastly exceeded the speed with which our culture has absorbed their impact. Therefore, we reasoned that as a first and small step toward preparing our students for the future that awaits them, by evaluating only a small number of common variants of only three genes, rather than the full set of 22,000 genes, we would give a large number of Berkeley students the opportunity to “peek inside their genes” as a way of engaging them in a discussion about the science, the technology, the health, ethical and privacy issues surrounding personalized medicine. It should be a great learning experience.

We considered sending out a book or set of magazine articles to provide the “study object” in advance of our discussion. However, we decided that involving students directly and personally in an assessment of genetic characteristics of personal relevance would capture their imaginations and lead to a deeper learning experience.

Of course our students, once engaged, are voracious learners. We are creating an electronic bookshelf of materials for them to read prior to coming to Berkeley that offers a means to consider the various voices surrounding the many and varied issues related to personalized medicine.

All students whether they are minors or not will be asked to provide informed consent. They will read and sign a detailed form describing exactly what will be done with their DNA sample, how the information will be used and secured for confidentiality, how this information might benefit them, and what the alternatives are to submitting a sample. This consent form has been reviewed and approved by the UC Berkeley Committee for Protection of Human Subjects Institutional Review Board. If the student has not yet turned 18, a parent must also provide informed consent and sign the form in order for the sample to be analyzed. Any samples we receive without a signed consent form will be destroyed without analysis.

Each student will receive two identical unique bar code stickers in the packet we are mailing: they affix one to the sample and keep the other. When we receive the envelopes, an employee (not a scientist) will open the envelopes and check the informed consent forms. If the informed consent forms are signed, those bar-coded swabs will be passed on to the scientists to analyze. If the informed consent form is not properly signed, the specimen will be destroyed and safely discarded. No identifying information beyond the bar code will accompany the specimens to the lab. After the analysis is complete, the results will be posted, by barcode number, on a website, where each student can check only his or her results. Thus, the only person who will have access to a specific individual’s test results is that individual. Only these three gene variants will be tested for and all remaining DNA from the specimens provided will be incinerated immediately. If a student loses his or her bar code, there will be no way for her or anyone else to access her genetic data.

The data will be kept in a database that the students have access to, and only they will be able to decode which information is theirs. Because this is an educational program, the aggregated data will be presented to the students in Professor Rine’s lecture, emphasizing how information about groups differs from information about individuals. As noted above, the University will not have information linking specific sample results to individual students.

This project has been reviewed and approved by Berkeley’s Committee for Protection of Human Subjects Institutional Review Board.

Instructions provided to students will emphasize that participation is completely voluntary and that the identity of students who do and who do not participate will not be known. Regardless of whether or not they return a DNA sample, all students will be invited to attend a presentation by Professor Jasper Rine at the beginning of the Fall semester and the various discussion panels and other events organized around this program so learning may occur regardless of personal participation. Since we will not know which students submitted samples and which did not, there will be no opportunity for prejudice or pressure on students to participate. We fully expect that some students will choose to participate and some will not. This will provide a perfect example to them, at the earliest stages of their college experience, that smart, well-informed people, their peers, can make different and equally defensible decisions on important issues like genetic testing. We believe this experience will have value in the context of many issues that they will debate in this program and others and in their future lives.

Commercial DNA tests examine a large number of genetic markers, many of which are associated with serious diseases including cancer, diabetes, heart disease and kidney failure. There is active debate in the public about the appropriateness of providing personal genetic information about disease predisposition in a non-medical setting. In the case of the UC Berkeley program, we propose to test for three common genetic variants that are not indicators of disease per se, but rather represent variation between individuals in how they metabolize various nutrients. We will thoroughly describe the significance of these three gene variants to students in writing before they submit their specimen, in a lecture delivered by Professor Rine at the beginning of the Fall semester, and again in the form of a PDF file downloaded along with their individual test results. Finally, either Professor Rine or Dean Schlissel will meet individually with students interested in discussing their test results.

Keep in mind that technology can advance faster than cultures respond. With respect to personalized medicine, our country trains far too few genetic counselors to handle the flood of genetic information that is coming, and our medical students have curricula that are already packed with important information. We see a large gap developing between our ability to produce genetic information and the ability of the conventional medical establishment to assimilate, explain and utilize this information. In the near future, we think that individuals may have to take a more active role in the management of their own health care, informed by their genetics. We hope to provide our students an opportunity to take a small step in that direction. Moreover, we hope that this step is joined by our colleagues at other institutions as we try to learn how the shared genetic history of humanity can be interpreted for the benefit of all.

There will be no cost to students for the program. The final cost of the program is not known because we don’t know how many students will choose to participate and provide samples and we have not selected the commercial lab that will perform the testing. We believe that engaging a commercial lab or a fee-for-service core facility in an appropriate academic institution offers several advantages such as economies of scale, and low and robust estimates of error rate. However, we anticipate the cost to be similar to that of previous On The Same Page programs and regardless of the ultimate cost, there will be no cost to students.

No, they will not.

No, Berkeley neither endorses nor condemns direct-to-consumer DNA testing or any particular company operating in that marketplace. We think that genetic testing in general raises important issues that merit broad discussion. These issues will be a part of our Personalized Medicine theme.

We had initially intended to use product donated by a commercial DNA testing company as a prize in a contest related to this program. We have reconsidered this aspect of our project, and decided not to offer this as a prize so as to avoid the appearance of endorsing a particular company or being perceived as taking a position on the issue of direct-to-consumer DNA testing.

No. Professor Rine and the other organizers of this program do not have any conflicts of interest with regard to this project. The genes we are testing are different from the genes Professor Rine studies in his lab, his lab will not be performing the genetic tests, and neither he nor the other organizers will personally profit from this program in any way.

Professor Rine has been involved in multiple biotechnology companies since the early 80’s. It is common for UC faculty in multiple disciplines to be engaged in the interface between basic research on the campus and the development of applications of that research in the private sector. Indeed, the high tech sector of California’s economy has been driven in large part by innovation at multiple UC campuses and by our colleagues at private universities and national labs. The high-tech sector has provided career opportunities for many UC graduates and is an important part of our economy.

Presently, Rine is involved in a company that is trying to find the genetic basis of neural tube defects (NTDs), a common and often severe type of birth defect, which his lab is also studying. The company, called Vitapath Genetics, is located in Foster City. Rine was one of four founders. His lab gets no research support from the company, and UC holds the patents on anything he discovers, which the company would have to license. If the genetic cause of neural tube defects is found, the company will offer a genetic test that will help people avoid having NTDs in their children.

Professor Rine’s involvement with human genetics-related companies began in the the early 90s. He played a small role in cancer gene research through Myriad Genetics, and in the past served on the Affymetrix, Rosetta, and Perlegen scientific advisory boards.

Frequently Asked Questions: Students

Sending in a sample is both entirely voluntary and fully anonymous. Since returned samples will be labeled with a bar code that only the student participant will know, the deans and faculty will have no way of knowing who sent in a sample and who did not. Regardless of whether you return a sample, you will be invited to participate equally in any event associated with the OTSP program. We will also solicit all students to participate by sending us an essay, poem, or other creative piece of relevance to our theme early in the fall semester.

We decided to invite you to participate in this voluntary limited genetic test in the hope that it would provoke you to think more deeply about the rapidly increasing role of DNA analysis in decisions involving your health and medical care. Also, you will get a sense of the types of information that analysis of your genome can reveal. Even the process of deciding whether you want to sign a consent form and send in a sample is part of this educational program.

No. We will test your DNA sample only for the presence or absence of three common gene variants. The remaining sample will be destroyed.

The human genome is made up of about 3 billion bits of information in the form of nucleotides, symbolized by the letters A, G, C, and T, which make up DNA. The DNA in your genome codes for tens of thousands of genes. Each of these genes provides the information code that allows your cells to make a particular protein. This code of A’s G’s C’s and T’s is greater than 99.9% identical from person to person, but it’s the tiny differences that contribute to the uniqueness of each person. In each of the three genes we are testing, some people have a one-nucleotide difference from other people (a T instead of an A, for instance, at one particular place). Something as seemingly minor as a one-letter difference in a 3-billion-letter genome can change an encoded protein in a significant way.

The first gene codes for an enzyme called lactase that is necessary to digest milk and milk products properly. All of us make this enzyme in childhood, but most people stop producing it in adulthood, making such people lactose intolerant. People with lactose intolerance experience gas and bloating when they consume too much milk or cheese. A fraction of people (~10-20%), however, have a variant of the lactase gene leading it to remain active into adulthood. These people have no trouble digesting milk. We will test your DNA to see which form of this gene you have. You should be sure to eat foods rich in calcium and be sure you get enough vitamin D regardless of which form of the lactase gene you have.

The second gene encodes an enzyme called aldehyde dehydrogenase. This is one of a series of enzymes involved in metabolizing (digesting) alcohol. We will test for a variant of this gene that is associated with flushing (red face) and nausea after drinking alcohol. Since most of you are below the legal age for drinking alcohol, we strongly suggest that you not drink regardless of the results of this gene test.

The third gene codes for an enzyme called methyltetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR). This enzyme uses the vitamin folic acid to convert a metabolite called homocysteine into an amino acid called methionine. About 9% of people have two copies and 40% have at least one copy of a variant of the MTHFR gene that decreases enzyme activity resulting in a modest elevation of homocysteine levels in the blood. Very high homocysteine levels can cause health problems, while there is debate but no consensus on the effects of the modest elevations associated with this very common gene variant. Eating a diet rich in folic acid (found in leafy green vegetables) or taking a vitamin pill containing folic acid (vitamin B9) results in a decrease in homocysteine levels to the normal range.

We will provide information in written form when you retrieve your test results online in September. Also, Professor Rine will discuss the meaning of these results in his featured OTSP lecture in September. In addition, Professor Rine would be happy to meet individually with any student interested in discussing these test results. Finally, we are working on organizing genetic counseling, free of charge and by appointment, through the Tang Center here on campus for anyone desiring further information about his or her test results.

To our knowledge, this kind of educational program offering gene testing to an entire incoming class has never been done before. Observers are concerned about making certain that participation is fully voluntary and anonymous, that everyone who returns a sample has given his or her proper informed consent and understands what we are testing for, that we have scrupulously protected students’ privacy, that no other tests will ever be performed on your DNA sample, and that we provide you with adequate information and counseling to understand the significance of your own test results. This project was considered and approved by the campus Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, which reviews all experiments involving human subjects at Berkeley; the Committee affirmed that this project takes proper account of each of these important issues. As always, it is a matter of personal choice whether to participate in such a study. If after reading this material you have any doubts, simply choose NOT to send in a sample.

DNA testing is used in our society in many different ways. The ways you think about it may be shaped by contexts in which you may have encountered it before. Genetic testing can be used in medicine to estimate an individual’s risk for certain diseases or conditions. In prenatal diagnosis, a sample of a baby’s DNA can be tested early in a pregnancy if parents are concerned about genetic disorders. In forensic testing, DNA is used to identify people (e.g., paternity testing or identifying human remains). The state of California maintains a forensic database of DNA samples from all adults arrested for a felony offense. Commercial firms advertise ancestry kits that include DNA tests. The genetic test offered by OTSP looks at three specific genes that are linked to particular metabolic conditions. The information it provides has some medical significance. For example, women’s ability to get enough folic acid in their diet is very important if they get pregnant. While the test gives information that can help identify you by your genes, it is not possible to use the results to create a full forensic profile. It is indirectly possible to get some information about ethnoracial identity, since at least one of the genes involved (for lactose intolerance) is distributed differently across ethnoracial groups.

DNA testing for medical conditions is scientifically well established for some important diseases, such as certain types of cancer (for example, variants of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes for one particular kind of breast cancer). There is debate about the utility of screening for particular genes for some other diseases, since there are many steps intervening between the gene and its expression. In recent months there has been a lot of discussion in the news media of “direct- to-consumer” genetic tests. These commercial tests give consumers information about their genes that is potentially medically relevant without going through a physician. Following on some controversy, DTC genetic tests are now expected to be brought under regulation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Personalized medicine, like much else in the realm of basic and applied research toward health care innovations, involves for-profit companies and patents. Some people are concerned that the future of personalized medicine is driven too much by these forces. Others are concerned about the potential cost of personalized medicine, which may limit how accessible it will be to all patients.

Confidentiality and anonymity are important in connection with the privacy of your genetic information. The uses of private genetic information have been an issue in recent discussions of DNA testing. For example, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimation Act of 2008 (GINA) was passed in response to concerns that health insurers would charge people higher premiums, or employers would refuse to hire them, if they knew that genetic testing had shown they had a predisposition to developing a disease.

Ownership and use of genetic samples and data have also been debated in recent discussions about the ethics of biomedical research. For example, the Havasupai Indian tribe recently settled a lawsuit with a university that had done scientific research on tribal members’ DNA that was different from the research on diabetes for which the DNA had been donated and not acceptable to the donors when they found out. It is possible that our society is in the middle of important changes in how we understand the standards for anonymity and for ownership of genetic samples and information.

Informed consent has become an ethical requirement for conducting scientific research on human beings. Meeting this obligation requires that potential participants (“human subjects”) have been provided and have comprehended information that allows them to voluntarily decide whether or not to participate. The procedures for obtaining informed consent are described in the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations. They form the framework for the consent form in this package. At each university or other institution that conducts research on human beings, informed consent is overseen by an Institutional Review Board. The Institutional Review Board at Berkeley is the Committee for Protection of Human Subjects.

Informed consent is a process, not just a form. How informed are you? Giving informed consent is not simply a matter of understanding the genetic markers you might agree to be tested for. Other questions you might ask include: Who is inviting you to do this? For what purpose? What do you hope to gain from agreeing to participate? With what consequences?

Informed consent happens within a social context. Is your choice affected by expectations about what other people want you to do? By how you think other students may view your decision (if you share it with them)? Will the testing impact your family? Do you have personal experience, or do you belong to a group that has experience, with other kinds of DNA testing? Does this shape how you react?

Letter from Dean Mark Schlissel to Community Member

Letter from Dean Mark Schlissel to Students

August 13, 2010

Dear Students,

I am writing to you about some changes we’ve been directed to make to the College of Letters and Science’s On The Same Page — Bring Your Genes to Cal program. The idea behind this teaching program is to welcome you to the academic community at Cal by inviting you to participate in a series of discussions about Personalized Medicine, the set of rapidly improving DNA based technologies that will allow physicians in the years ahead to better prevent, diagnose and treat disease by using the information available in a person’s own DNA. As you may recall, last month we sent you information about the program, along with a saliva collection kit and a consent form. We offered you the opportunity to, on an entirely voluntary and anonymous basis, send in a sample of your saliva from which we would purify DNA and then test it for each of three common gene variants affecting your ability to metabolize milk products, alcohol, and the vitamin folic acid. We had promised to allow those students who sent in samples to obtain their test results after a series of educational events we have planned for mid-September including a lecture in Wheeler Hall by Genetics Professor Jasper Rine.

Since this unusual education program involved testing human material, we sought the opinion of Berkeley’s Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS) who approved our plans as well as the wording of the consent form we sent you.

This program has generated a large amount of public interest and debate, covered extensively in the news media. Some people think that it is inappropriate to solicit DNA samples from incoming students for this purpose regardless of the privacy safeguards we put in place, CPHS approval, and your informed consent. Others think this to be a very creative way to engage our students in thoughtful consideration of a series of important and timely issues.

Earlier this week, we were informed by the California Department of Public Health that they consider these DNA tests to be medical tests, and that we are not allowed to return individual results to you unless the tests had been ordered by a doctor and performed by a licensed clinical testing lab. This ruling relies on an interpretation of legal statutes that is entirely different from the interpretation of the same statutes by UC’s top lawyers. However, we must, of course, follow the interpretation of the statutes by the agency charged with their administration. Since the three genes we are testing are not routinely tested in medical practice, we were unable to find a licensed clinical lab to perform these tests and of course, a physician did not order them.

Thus, I am very sorry to inform you that we will not be able to give those of you who submitted samples access to their test results. Nonetheless, we currently plan to analyze the samples in a research lab on campus and present the aggregated results to you during Professor Rine’s lecture. The remaining DNA would then be destroyed as promised. In order to do this, we must first seek the permission of the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects since this represents a significant change to the plan that they originally approved. If they deny this request, then we will have to destroy the samples and not perform any analyses.

The public controversy generated by the OTSP program and the decision of the California Department of Public Health raise a series of fascinating issues that will be included in the conversation we will all have when you arrive on campus. If you have any questions before then, you can contact Alix Schwartz at alix@berkeley.edu.

We hope that you each had a wonderful summer and look forward to seeing you all on the Berkeley campus very soon. Be on the lookout for more information about On The Same Page — Bring Your Genes To Cal events when you arrive.

Sincerely,

Mark Schlissel M.D., Ph.D.

Dean of Biological Sciences

Learn About—and Discuss—Personalized Medicine

Enroll in a Freshman and Sophomore Seminar related to the theme in fall 2010.

Take a class from a faculty member who is incorporating our theme into one of his or her regular fall courses.

Freshman and Sophomore Seminars

The following courses, open only to first- or second-year students, provide small, interactive, credit-bearing contexts in which to discuss the theme.

Fall 2010

Integrative Biology 24, Section 1: Biology: The Study of Life (1 unit, P/NP)

Professor Tyrone Hayes

Mathematics 24, Section 1: What is Happening in Math and Science? (1 unit, P/NP)

Professor Jenny Harrison

Molecular and Cell Biology 90A, Section 1: Your DNA (1 unit, LG)

Professor Jeremy Thorner

Molecular and Cell Biology 90D, Section 2: Personalized Medicine—DNA, Healthcare, and Privacy (1 unit, P/NP)

Professor Mark Schlissel

Vision Science 84, Section 2: Current Topics in US Healthcare (1 unit, P/NP)

Professor Kenneth Polse